Issue 05: Her sister has autism. Here's what she wants you to know.

The stigma of autism in one South Asian community

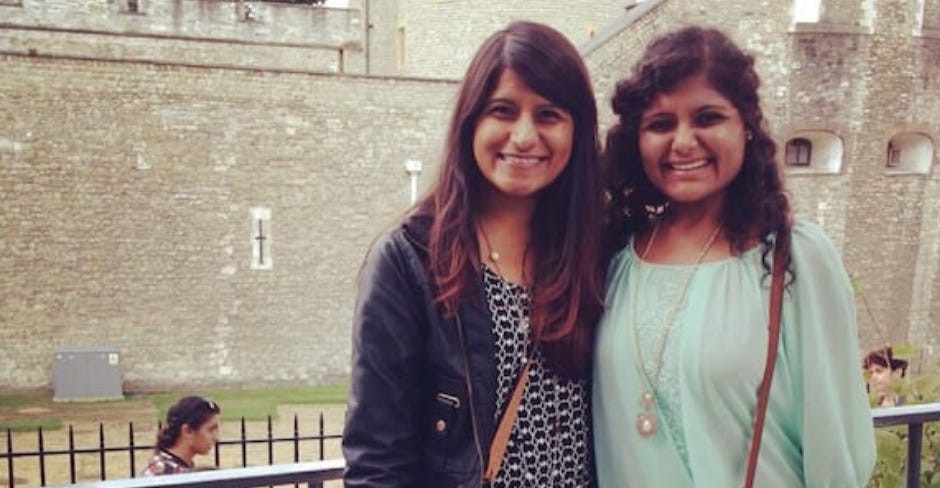

Sehrish (left) and her younger sister Shazia (right) moved to America from Karachi, Pakistan back in 1999, ultimately settling down in Atlanta.

Growing up, Sehrish and her family couldn't figure out why Shazia was struggling so much with her grades. She'd already been held back twice before middle school. Because she was taking ESL classes, teachers assumed her poor academic performance was simply due to a language barrier.

Then Shazia met Ms. Davis, a 7th grade special education teacher. In 2005, with the guidance of Ms. Davis, Shazia was officially diagnosed with Asperger's and autism spectrum disorder.

But acceptance hasn't come easily.

Sehrish had trouble getting her parents, her dad in particular, on board. He'd blame her for her mood instability or erratic behavior, common symptoms of ASD, saying it's all because Sehrish didn't include her in all her social gatherings and intentionally ostracized her. It wasn't a disability to him. It was a problem with a simple fix: sisterly love.

It's true that when Sehrish was younger and knew little about the spectrum, she felt detached from her sister. Despite being just a year apart, Sehrish couldn't seem to connect. Shazia wouldn't laugh at the same jokes or respond appropriately in conversations. As a teenager, Sehrish felt no one would want to hang around her if she brought Shazia around. So she didn't.

Sehrish continued to internalize the guilt. When Shazia would get laughed at or bullied in her religious education classes, Sehrish blamed herself. Perhaps she could have been more supportive. A better sister. Eventually, mom and dad began to exert blame on themselves, too.

It was easier to believe she was struggling because of them. Simply admitting she's struggling and always will was far too painful.

But over the years, Sehrish and her family have been slowly learning to acknowledge that some things just aren't under their control.

The family relied on the few people they knew for help, a culmination of teachers, family members and religious institutions. But what little money they were able to conjure up through Medicaid led them to services that just weren't up to par. Multiple therapists resulted in multiple diagnoses and re-diagnoses. Still, mom was relentless. A champion for Shazia through the pain, she sought help from everyone she could reach, encouraged Shazia to begin medication and attend therapy sessions twice a week.

And this May, 14 years after her initial diagnosis in 2005, Shazia will be graduating from college.

As an adult, Sehrish has learned more about autism and her younger sister's unique world. Their first one-on-one time? Just a few years ago, when Shazia visited Sehrish in Austin, Texas. Since then, the pair's traveled the world together, devoured Belgian waffles in Brussels and learned to appreciate each other's quirks. Fun fact: Shazia is a hardcore Bollywood film buff and can identify every actor and movie plot from any year.

Everything Sehrish was, is and wants to be has been shaped by her relationship with Shazia. While the stigma still stings—mom and dad still implement the "don't ask, don't tell" policy—Shazia's skills and progress leave her beaming with pride.

When she reluctantly introduced a significant other to her little sister this year, Sehrish didn't know what to expect. Shazia reminded her that happiness is a blessing. And blessings should always be shared with the ones you love.

Sehrish is a graduate of Emory University and the University College of London. After teaching for three years, she'll be pursuing a doctorate in educational psychology, specializing in special education with a focus on autism spectrum disorders. She begins this fall.

Here's what she wants you to know:

Sheer compassion can really start to change things. And that comes in a two-part process. First, learn about autism spectrum disorders and spread the word. And second, learn to be okay and comfortable with individuals with autism. Promote hiring and training them, open college programs to include them, invest in valuable school support services early on. Everyone deserves to live a life of respect and dignity. Everyone.

Q&A

Meet Sehar Ali, a Board Certified Behavior Analyst Intern and Registered Behavior Technician based in Houston, Texas. She has worked with children on the spectrum for five years now.

How often do you work with immigrant children on the spectrum?

Of the 12 patients that I currently work with, a little over half of them are first generation American. Their families come from a variety of countries including Mexico, India, Iran and Nigeria. In the past, we have also had patients who moved specifically to the United States to get treatment for the child.

Do you notice differences in the ways immigrant parents approach situations vs. non-immigrant parents?

The answer to this is slightly complicated. The thing that we need to understand, and it took me some time to understand this as well, is that no parent, regardless of their immigrant status or education level or even understanding of developmental disabilities, wants anything to be wrong with their child.

But cultural expectations do affect how parents approach situations. For example, one of my patients, let’s call him Luke, is first-gen American and his parents were raised in Eastern Europe. As far as parental investment and willingness to work on therapy goes, these guys are superstars.

Another patient, let’s call him Peter, is Nigerian. Peter’s mom is totally on board with everything we discuss, but it took us a little longer to get his dad on board. Dad insisted that nothing was wrong, and that Peter was just a late bloomer and a rambunctious little boy.

A third patient from India has parents willing to accept the diagnosis for what it is but they remain extremely reserved about talking about their son's diagnosis outside of the clinic, which gets in the way of our collaborating with school teachers and speech therapists.

What do you wish you could tell parents reluctant to get help?

I wish that I could tell them to stop caring about what the rest of the world thinks or says about their child. None of that matters. As a parent, you know your kid better than anyone else and you know what they need.

What do you feel the public (or media) gets wrong about autism?

I wouldn’t say that media gets it wrong, but I will say that it is a little one sided. There are a lot of great TV shows out there (i.e. Atypical or The Good Doctor) that I think do a pretty good job of showing what it can look like when interacting with someone who has ASD and is high-functioning (emphasis on high functioning). Most people might think of Dustin Hoffmans’s character in Rain Man, but that is generally not the case. The most current statistic I could find said that 1 in 10 people with ASD have varying degrees of special skills, ranging from what we call "splinter skills" to "prodigious savant."

You're a Pakistani Muslim. What have you noticed about your own community's approach to ASD?

I see a lot of denial. A lot of it. And it’s really sad. In general, our community usually writes off individuals with disabilities as lost causes. I am doing my best to change that with the interactions I have with people in mosque but it is going to take a lot more than just one girl in one mosque to change the mindset of a whole community.

How can people learn more about autism?

The first place I like to send people is the Autism Speaks website. They have all kinds of information about ASD, treatment options, school resources, etc. Another way is to find events in your community such as autism walks. April is Autism Awareness months and a lot of places have events that everyone is invited to throughout the month. If you want to learn more about the diagnosis itself the National Institute of Mental Health is another great resource.

Are immigrants especially vulnerable?

Does migration actually play a role in autism? Maybe. A 2009 meta-analysis of 40 international studies examined factors that seem to track with an increase in autism risk. On the list: having a mother who was born abroad.

Here's more:

Swedish children with parents born in sub-Saharan Africa vs two native parents. A 2012 study on ~5,000 Swedish children on the spectrum found rates of autism with intellectual disability were nearly twice as high among children whose parents were born in "resource-poor" countries (in sub-Saharan Africa) compared with families with two Swedish-born parents. (British Journal of Psychiatry)

Intellectual disability most prevalent when born within one year after maternal migration. The 2012 study also found intellectual disability was most prevalent among Swedish children born within ~one year after their mothers moved, which may suggest stressful migration plays a role.

Children born to women in war zones especially vulnerable. In a similar vein, a 2014 study on 1.6 million LA County kids found children born to women from current or former war zones may be vulnerable to autism. Autism was 76% more common among children of foreign-black moms compared to white children of US-born moms. (Pediatrics)

In Australia, children of some African immigrant families at increased risk. This 2017 study of Australian children found children of immigrant families from East Africa were 3.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with autism with an intellectual disability compared to children of white moms. (Child Neurology Open)

Autism rates are unusually high among Somali children in Minneapolis, but we still don't really know why. An emerging theory: lack of vitamin D, which some research shows is imperative for brain development. (Scientific American)

Get involved in research. Here's a nationwide opportunity via Emory University:

"The nationwide research program All of Us, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, has now enrolled more than 100,000 participants in a historic effort to advance individualized disease prevention, treatment and care for people of all backgrounds. The goal is to enroll 1 million or more participants nationally." More here.

The barriers to getting help

In general, folks from immigrant backgrounds who have a child on the spectrum tend to have greater difficulties in "accessing, using, and complying with intervention services for their child." (Journal of Child and Family Studies)

Why? So many complexities lead to misdiagnoses or lack of diagnoses! From stigma, communication barriers, culture clashes, lack of topical education...

And:

A fraught parent-clinician relationship: Immigrant parents often perceive interventions from healthcare professionals regarding delayed child development as offensive. (Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry)

Quick dismissal of classic autism traits as cultural differences: Anecdotal evidence has found results of routine school screenings didn't line up with official evaluations by clinicians because interactions "were tinged with cultural confusion" or written off as language barrier issues. For one Minnesota patient, misinterpretations during an official medical evaluation after the school screening led to no diagnosis. The patient was indeed on the spectrum, as subsequent evaluations noted. (Scientific American)

Gender clash in parental intervention: Moms of children with ASD tend to focus on positive aspects, while the majority of fathers tend to emphasize the child’s difficulties. This tends to make an already challenging experience much more challenging in the household. (Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry)

Fear of losing hope: Immigrant moms may fail to acknowledge ASD diagnoses in their kids as an attempt to preserve hope for the future "instead of having to accept that their child had a disorder associated with more long term disabilities." Instilling hope is, therefore, essential to parental investment. (Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry)

Costs: According to the CDC, on average, medical expenditures for children or adolescents with ASD are 4.1-6.2 times greater than for those without. In 2005, average annual medical costs for Medicaid-enrolled children with ASD were $10,709 per child, ~six times higher than costs for children without ASD ($1,812). And in addition to medical costs, intensive behavioral interventions amount to $40K-$60K per child, per year.

This painful Splinter piece from Katy Reckdahl tells the story of Christopher San Martin, a 6-year-old in New Orleans who physicians and therapists believe is likely autistic. Christopher's loving father, who is undocumented, is being detained at an immigration facility and faces deportation. Read here.

In this AJC story titled "Nuestra Comunidad" Johanes Rosello of Mundo Hispanico talks to Hispanic parents in the Atlanta community with children on the spectrum and how lack of community knowledge about autism makes life that much harder. Read here.

The Atlantic's Jocelyn Wiener and Kaiser Health News published a story back in 2017 addressing the deportation fears of immigrants with disabled children. If the parents are picked up by authorities, what happens to the kids? Read here.

Angie Kim's debut novel "Miracle Creek," has been dubbed a "courtroom thriller." Kim, who left South Korea for America as a child, is a former trial lawyer. In her book, she tells the stories of a group of women whose children have autism. Listen to the NPR interview. Buy Kim's book here.

This 2018 radio interview on 89.3 KPCC talks about how having a child with autism or any developmental disability isn't easy, but in some immigrant communities, like Koreans, the stigma makes it even harder to get help. Listen here.

In this story for Spectrum, writer Emily Sohn addresses the gender gap in autism research, highlighting the story of West African immigrant Morénike Giwa Onaiwu, who grew up showing signs of autism without realizing what made her so different. Today, she's co-executive director of the Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network and chair of the organization's Autism & Race Committee. Read here.

Interested in helping fact-check this newsletter? I could use the help! Just want to send some feedback? Email away! fiza.pirani@gmail.com.

A very special thank you to Sehar and Sehrish for sharing their stories.

Foreign Bodies is a monthly e-mail newsletter dedicated to the unique experiences of immigrants and refugees as they relate to coping with mental illness and wellness. It’s written and curated by Atlanta-based writer Fiza Pirani with copyediting and fact-checking help from New Jersey-based independent journalist Hanaa’ Tameez. Want to contribute your time or share your own #ForeignBodies story? Send an email to 4nbodies@gmail.com or say hi on Twitter @4nbodies. Special shout-out to Carter Fellow and friend Rory Linnane for the adorable animated logo!